Felix Yusupov's autobiography reads like the libretto of an opera. Prince Yusupov was the descendant of both the Crimean and Nogai khans, of Mohammedan origin, and belonged to a family that had come to prominence in Muscovy much later than most of the great families of Russia. They were close to the tsars and were showered with wealth and marks of favor, although at the same time remaining under the radar to some degree. Indeed, Felix Yusupov himself, the last of the line, would become the most famous member of the Yusupov family, which was allegedly the wealthiest private family in Russia prior to the Revolution. They owned two large palaces in that fantastic metropolis of decadence and excess, St. Petersburg, the larger of which included a private theater. In fact, it would be at this latter palace that Felix Yusupov would stake his claim at infamy and which would lead him to his lawsuit against MGM in 1932. Felix Yusupov was one of three men involved in the assassination of Grigori Rasputin, which MGM depicted in film, although it was not the prince’s depiction that resulted in the lawsuit. Felix sued because of the portrayal of his wife, Princess Irina of Russia, who was presented as having been seduced by Rasputin. And Felix won the case based on this slander of his wife. Indeed, one wonders if Felix Yusupov cared about how he himself was depicted.

At the time of Felix's birth in 1887, the Yusupovs were on the verge of extinction. His mother, Princess Zinaida Nikolayevna, was the only daughter of the sole remaining Prince Yusupov. Princess Zinaida's husband, Count Sumarokov-Elston, was permitted by the Russian Court to take the Yusupov name and therefore to continue the family line. Felix himself was the second of the couple's two sons. He'd been sent to study at Oxford after establishing a reputation for being a kind of Edwardian enfant terrible. Notably, Prince Yusupov's resume of controversial acts included dressing in women's clothes and passing so convincingly as a woman as to cause some difficulty for those attracted to him. The story goes that the only way that the police were able to discover that the beautiful woman who had caused a disturbance at a nightclub was Yusupov was because the diamonds that he had dropped during his flight were recognized as belonging to his family. Felix would cause further shock when he returned to Russia in 1913 and became the desired spouse of Princess Irina of Russia, the daughter of Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, the sister of Nicholas II. Nicholas II reluctantly permitted the marriage, which brought Felix into the family circle and therefore placed him as the perfect person to do something about that dangerous monk Grigori.

This is actually the 5th Marquess of Anglesey and not Yusupov, but I imagine Felix as being something like this when in female attire, although obviously sans mustache.

One wonders if Felix saw himself as a kind of savior of Russia. In "Lost Splendor," his autobiography, Felix Yusupov almost seems to suggest that his lineage is no less august than that of the House of Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov, or simply the House of Romanov. Felix conspired with Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich and Vladimir Purishkevich to assassinate Rasputin by first inviting him to the Yusupov family's Moika palace and then poisoning him. It is important to note that there had been calls at this time to overthrow Nicholas II and replace him with another member of his family, in part because of the association of the Romanovs with Rasputin, widely believed to have the family completely under his spell. Therefore, one can speculate that there might have been some talk in the family that Yusupov might be the perfect person to murder Rasputin and save the honor of the family, since he was technically only a member of the family by marriage. As only the spouse of a Romanov princess, Yusupov would not impugn the family with the accusation of murder. We all know how fickle the masses can be. One minute they want Rasputin murdered and the next they want the murderer hanged.

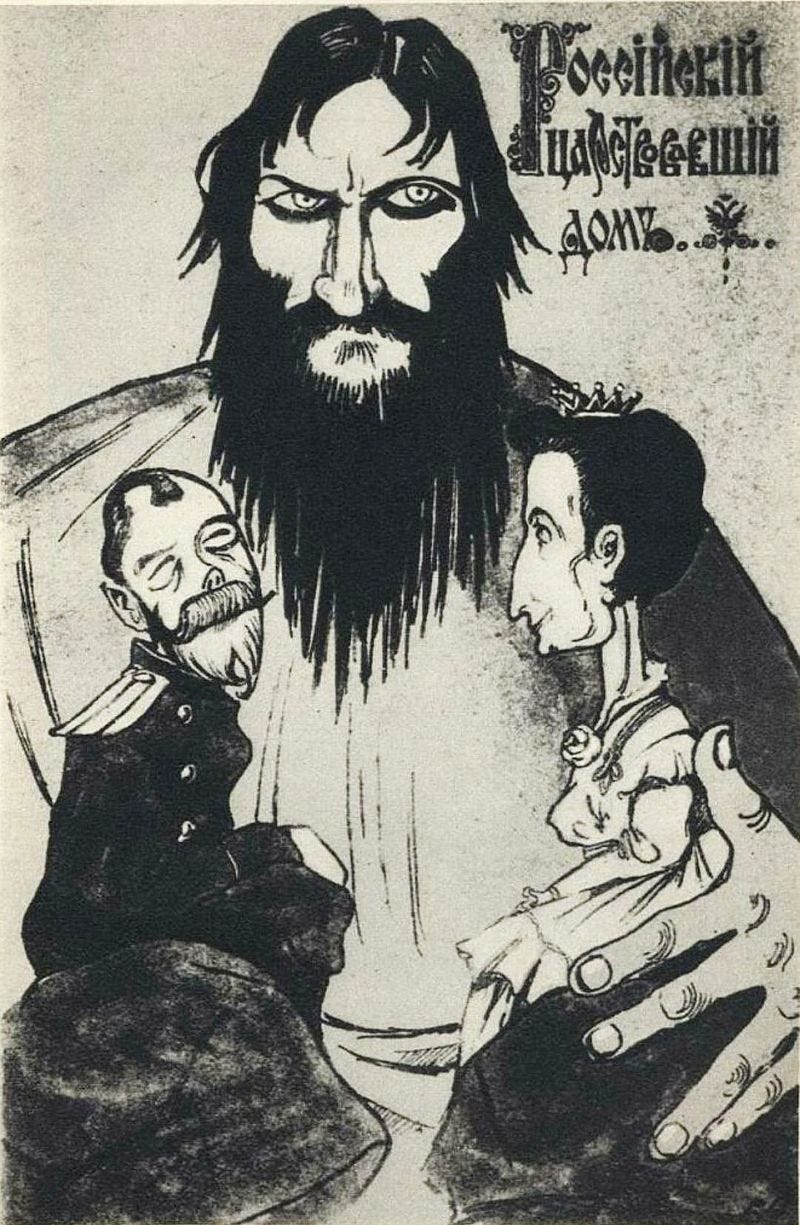

Rasputin was believed to have a magical hold on his human puppets, Nicholas II and Alexandra.

But this post is really about Yusupov's case against MGM, which had important implications. The film in question, “Rasputin and the Empress”, was released in 1932 and appears to have been mostly forgotten. The film appeared to depict true events, which can be construed as a form of slander against the real persons depicted. These depicted persons included not only Prince Yusupov himself, but his wife, a niece of the Tsar. Many of the other persons involved had lost their lives in the Revolution and its aftermath. The Yusupovs were awarded the then fantastic some of 25,000 pounds (one has to remember that a gentleman at the time could live on 500 to 1000 pounds a year), and the case led to the disclaimer that now appears at the end of most films: "The preceding was a work of fiction, and any similarity to names of persons living or dead is entirely..." I think you know the rest.

And since everyone is presently obsessed with AI and LLMs (large language models), I can only imagine what ChatGPT believes the origin of movie disclaimers is. I daresay there won’t be any mention of Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina. It won’t be long before people like them are entirely forgotten.

Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich who, like Yusupov, survived the Revolution.

So I put said movie disclaimer forward to Chat GPT 4o, and it says: 'By the 1930's, the use of such disclaimers became a standard practice.." and "One famous case that underscored the need for such disclaimers was Bindrim v. Mitchell (1979)...". No mention of Felix at all. I then put this forward:

===When did felix yusupov pass away===

\\\\\\Felix Yusupov passed away on

September 27, 1967.\\\\\\

===It is sad he didn't get to hear that great track===

\\\\\Yes, it is indeed interesting to consider. Felix Yusupov's life and the historical events he was involved in, particularly the assassination of Rasputin, have continued to fascinate people long after his death. The Boney M. song "Rasputin" certainly contributed to the pop culture legacy of those events, but Yusupov passed away over a decade before the song's release in 1978.\\\\\