I was watching a dramatization of Flannery O'Connor's The Displaced Person, and I was thinking about how issues of class and identity are handled differently in British TV and film as contrasted to the US. Yes, this is partly a manifestation of basic differences in American and British art, but it's also this idea that what class means in Britain has historically been different from the same construct in the US, particularly this idea that in America race has traditionally been viewed as a proxy for class. That's a little too heavy of a discussion for my taste and outside the purview of this Substack probably, so I'll just say that, for me, a film that I'd earlier seen called Penda's Fen helped my understanding of this difference take shape, as well as helped me take not of tricks that artists can use to address issues of identity in a nuanced way.

As a caveat to understanding Penda's Fen, I need to discuss The Displaced Person by Southern writer Flannery O'Connor, which I've already mentioned. Many great writers of Irish heritage have come from the South, and this is perhaps due to their interesting status as being in a sort of limbo in the traditional Southern class system, which dated from colonial times and was overwhelmingly Protestant. Interestingly, O'Connor examines someone else in limbo in the person of a post-World War II immigrant from Poland who takes a farming job on a large farm in the Deep South, where he is regarded with suspicion by everyone. The white trash, as they were called, see him as there to displace themselves with his tireless work, while the owner of the farm perceives him as intractably foreign and difficult to understand, preferring her Colored workers, as to her they comprise "the devil she knows." In the end, this displaced person, called Gobbledygook by some because they can't pronounce his Slavic surname, ends up being the victim of a Tolstoyan death, being run over by a tractor. Finally, the farm is sold, which leads to all of the workers, white trash as well as Black, becoming themselves displaced when the farm goes up for auction.

Flannery O’Connor on the far right (1947).

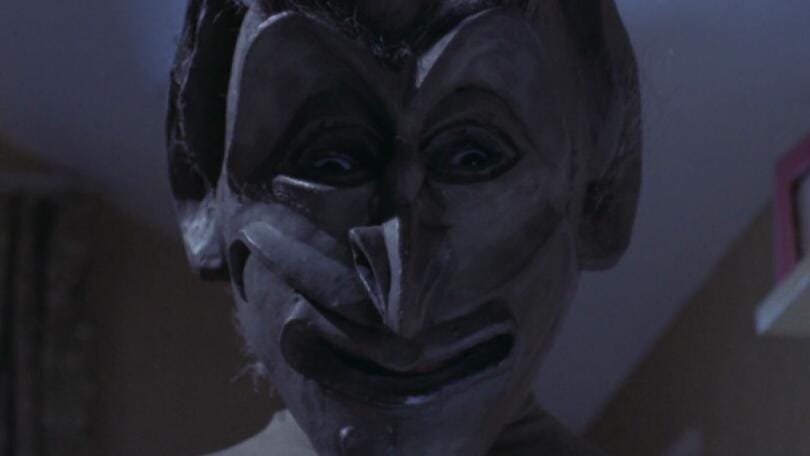

The Displaced Person is really a not-so-nuanced story about class in the changing times of the ‘40s and ‘50s, in my opinion. Perhaps everyone will be displaced in the world of modern technology, the story suggests. The tractor that slays Gobbledygook is a stand-in for Anna Karenina's St. Petersburg train. The Displaced Person is more subtle than say McCullers's book The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter, but not so subtle as a work like Penda's Fen. Penda's Fen, a TV film that aired on the BBC in 1974 and was directed by Alan Clarke, does something highly unusual in posing a question about the pre-Anglo-Saxon origin of Britain. It does this by examining the case of a fictionalized, outcast British schoolboy called Stephen. This film is remarkable because it represents an early example of British directors and screenwriters diverging from the conservatism of traditional British pictures, in films like Goodbye, Mr. Chips or shows like To Serve Them All My Days or The Horseman Riding By. It's as if someone stared at Stonehenge and the pre-Norman artifacts in the British Museum and asked themselves, "Who were these people? Have they been erased?"

The world of the British schoolboy isn’t so easy with bullies at every turn (if films and TV shows are to be believed).

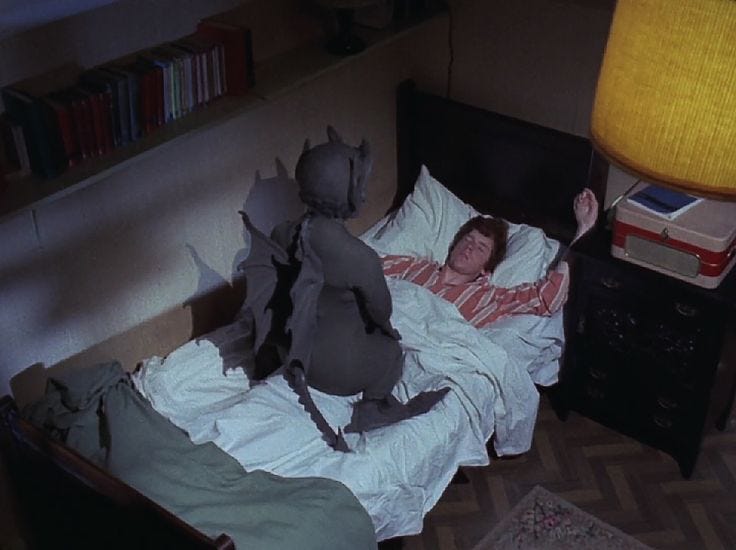

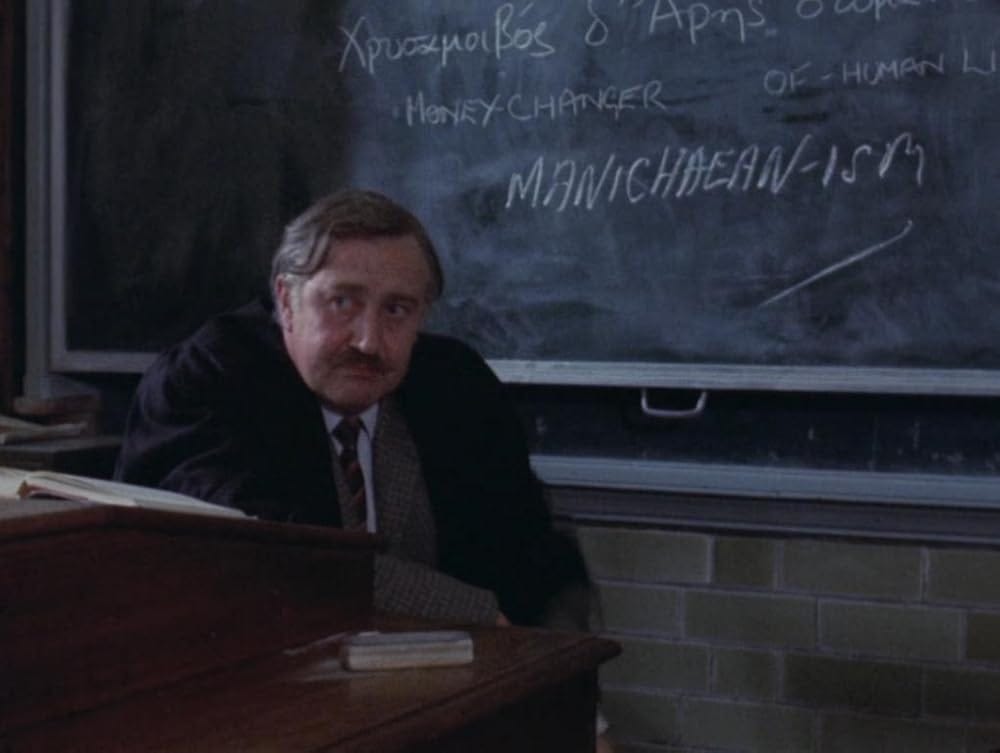

Penda was the name of a 7th century Anglo-Saxon king, and Penda's Fen explores aspects of this idea of a pre-Christian England. It begins with the protagonist, Stephen, existing (basically) in the familiar world of the British schoolboy: a world centered on strict schoolmasters and a distant C of E minister for a father. But Stephen's inevitable change begins in the form of what one of his teacher's labels a Manichean dream, in which Stephen visualizes what his teacher interprets as a battle between good and evil that resembles ideas that were early on purged from Christianity. Stephen's world unravels in both a mental and a physical sense, and it does so in a fashion that resembles that of Catherine Deneuve's character in Repulsion. We see surreal visions, like that of a father chopping up the limbs of his children on a table and people bursting into flames suddenly only for the flames to be put out mysteriously afterward.

I'm not the sort of Substack movie writer who likes to pen ten paragraphs explaining films in gross detail, with my own little two cents added, because I think when all's said and done each person should watch a film and take what they like from it. I just bring these films up because I think it's worthwhile watching them. Of all the films I've watched, I think Penda's Fen is among those most deserving of being watched broadly because of how singular it is, how effortlessly and honestly the unfamiliar themes are handled, and because I think it's unlikely that readers have heard of it. Penda's Fen has accomplished something that more recent films, both American and European, have failed to accomplish, which is presenting marginalized ideas in such a way that the viewer doesn't feel as if they are being clubbed over the head by a proselytizing acolyte.

Stephen's religious fervor, national pride, and sexuality are all questioned in the context of this idea of a pagan England coexisting with a latter Christian England. For, in essence, the pre-Norman, pre-Christian England never was erased, the film seems to hint. The question might be of an England engaged in a perhaps Manichean, perhaps Faustian battle with the modern day. But it's a question handled so well that you can choose to engage with it or ignore it entirely.

It must be pretty horrible to meet your sleep paralysis demon face to face.